Pradeep Kumar Panda

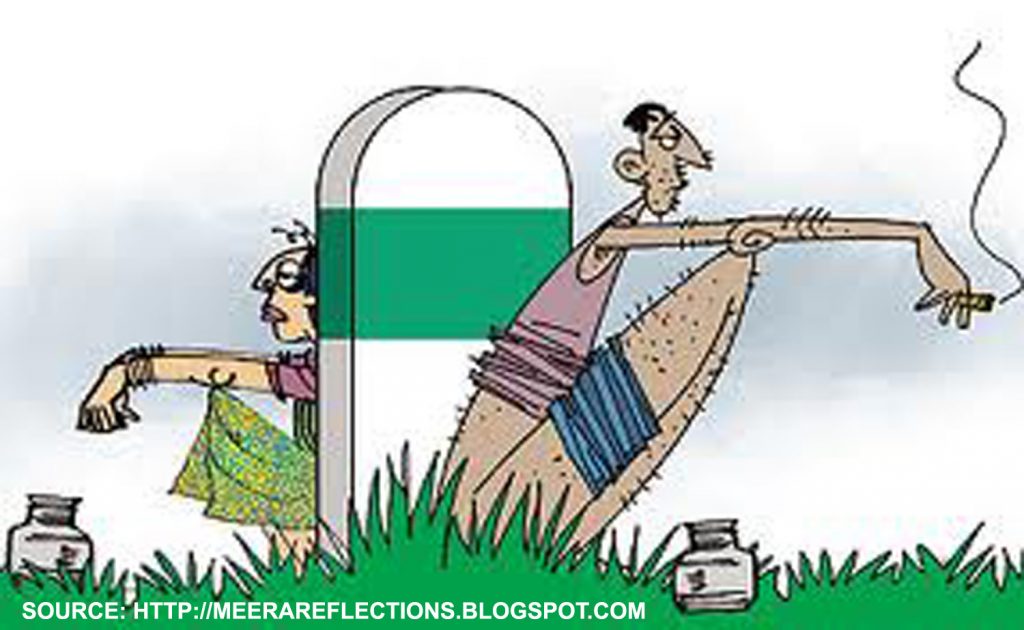

Open defecation poses significant health risks for individuals and communities across the globe. The practice affects vulnerable populations through diseases such as diarrhoea, schistosomiasis and trachoma, which often lead to stunting and malnutrition in children.

Open defecation is particularly prevalent in India, which is home to 59% of the 1.1 billion people in the world who practice open defecation. As per UNICEF, it is a major cause of diarrheal deaths among children under age five in India, and constituted 22% of the global disease burden in 2015.

To overcome the challenges associated with open defecation, we need, first, accurate estimates of its prevalence, and second, rigorous evidence on what works to promote latrine use. This information would be imperative to inform sanitation policy within and beyond the purview of the ongoing national sanitation campaign, the Swachh Bharat Mission (SBM), which aims to make the country free of open defecation by 2 October 2019.

There is dearth of rigorous evidence on what works to promote latrine use in India. There are several challenges of measurement of open defecation behavior in general and rural India in particular.

Measuring sanitation coverage and uptake is imperative to shaping policy in a country that hopes to be open defecation free (ODF) in a short span of time. Recent estimates provided by the Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation, and the National Annual Rural Sanitation Survey 2017 (NARSS), report that the SBM (rural) has been successful in improving latrine coverage and use by a significant margin since 2014.

Latrine use has typically been measured through the construction of latrines. This could be because the presence of infrastructure is relatively easy to verify. However, latrine presence does not necessarily amount to use.

Measuring the sustained use of water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) infrastructure is uniquely challenging in the midst of a nationwide campaign advocating for the importance of ‘correct’ defecation behaviour.

More recently, surveys have relied on respondent reported usage of toilet infrastructure, which can be prone to social desirability bias. Asking questions about inherently private behaviours such as defecation practices could elicit socially desirable responses, especially in ODF declared and verified areas.

For example, in the surveys that feed into the WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Program for Water Supply and Sanitation, such as the Census 2011, the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4) and National Sample Surveys (NSS), open defecation is deduced once all other forms of access to sanitation infrastructure have been negated.

Another challenge to the measurement of latrine use lies in the difficulty of adequately capturing variations within households. Surveys frequently fail to unpack usage to investigate individual latrine use due to resource constraints and logistical timelines.

Better understanding individual use is important, and a recent investigation of sanitation coverage, usage and health in India concludes that surveys that aggregated to the household level revealed lower levels of partial usage, while surveys investigating individual use found a higher incidence of partial use.

National surveys such as the Census 2011, the NFHS 4 and the NSS also tend to aggregate measured behaviour either to the household, sub-household or demographic group level, overlooking individual behaviour.

Learning from experiences in measurement, the NARSS measured both individual and subgroup latrine use. However, it subsumed latrine use into the categories of always, rarely, sometimes and never, conditional on shared and unshared latrines owned by households. This may lead to inaccurate responses, as the terms are not precisely quantifiable.

Whether or not a latrine is being used depends on water supply, which differs by season. Furthermore, the rainy season could deter many from defecating in the open. Dry season bias in household survey data collection coupled with seasonal shifts in sanitation practices, are likely to cause some distortion in reported use. In case of seasonality, respondents should be asked about their toilet usage in the recent past or within a specific time frame that can be accurately recalled.

There is no ‘right question’ to capture latrine use in rural India. However, survey questions can be designed in a manner that allows for triangulation to determine latrine use, where self-reported use may be combined with structured observations in sample areas, or in sub-samples.

These questions could also be framed while considering the nuances of seasonality and recall periods, and be administered at the individual level. These designs would have to be informed by evidence, the need for which has spurred a healthy debate among researchers and academics of late.

India represents an amalgamation of cultures, identities and social values that influence private behaviour currently under the spotlight. Much depends on researchers, implementers, policymakers and citizens to explore what works, why and in which contexts to reduce open defecation. This relies fundamentally on objective and balanced measures of the successes and failures of sanitation policy in the country.

The writer is an economist. e-Mail: pradeep25687@yahoo.co.in