“Embrace the trees and

Save them from being felled;

The property of our hills,

Save them from being looted.”

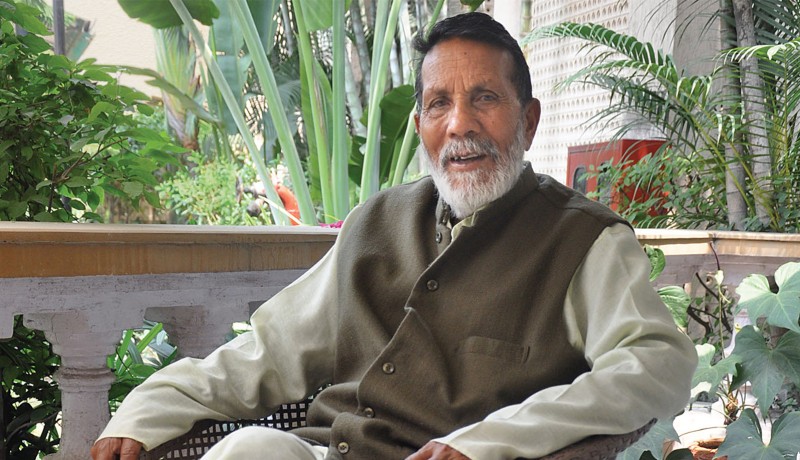

This was the slogan of the Chipko movement, a Gandhian satyagraha launched by Sunderlal Bahuguna and Chandi Prasad Bhatt in the Himalayan hills in 1973. For Bhatt, a man truly dedicated to the preservation of the ecology and environment of the Himalayas, environment is not just an abstract concept to be bandied about in seminar halls and drawing rooms but a living reality, inextricably bound with the daily life and struggle of the ordinary hill folk in the rural areas of Uttarakhand and other Himalayan states. Bhatt, who brought about an ecological awakening among the people of the mountains, was in Bhubaneswar recently to attend a felicitation programme. In a candid conversation with Sunday POST, he expressed concern over the drying up of rivers and talked about ways to prevent flash floods in Odisha in particular.

Aiming to protect trees from being felled, Bhatt made the women of the lower Himalayas realise why they were facing the problems of unusual drying up of water reserves and frequent floods. He says, “After all, it was women who were fetching water and collecting firewood. For instance, the Alakananda floods of 1970 inundated a 1,000 square kilometres of land in the hills and washed away many bridges and roads. I made the women realise that these problems arose because of the increased commercial forestry and resultant ecological degradation. Women of Uttarkashi and Gopeswar decided to launch a satyagraha by hugging the trees. The contractor’s men could not cut the trees and were forced to go away. This Chipko or hugging movement later spread to several other places in the Himalayan region.”

Bhatt’s journey began in a small village in Gopeshwar. He was just about two years old when his father passed away. Barring some income from a cow, farming, rent from an ancestral cottage and help from an elderly relative, there was no other source of livelihood. So, Bhatt could not afford college education. Instead, he taught Hindi and geometry for a year at a high school in Gopeshwar to contribute to the family kitty. After his marriage in 1955, his responsibilities increased. To meet his living expenses, he took up a job as a booking clerk with the Garhwal Motor Owners’ Union (GMOU) that operated a network of bus services in the region. While working there, he realised that there was more to life than merely earning a livelihood.

He says, “The year 1956 was a turning point in my life. Praja Socialist and Sarvodaya leader Jayaprakash Narayan visited the area with his wife Prabhavati while on his way to Badrinath. I instantly fell under his charismatic spell.”

Bhatt was also influenced by Vinoba Bhave. He remembers, “Bhave was to tour Jammu and Kashmir for a fortnight in 1959 and I joined his entourage. It was the experience of a lifetime and I felt spiritually rejuvenated. Then, in response to a fervent appeal by Jayaprakash Narayan for active volunteers in 1960, I made my ‘jeevan daan’ to the Sarvodaya movement.”

It was a life-changing decision as ‘jeevan daan’ turned him into a fulltime, lifelong dedicated volunteer working for the welfare of fellow human beings. “However, both my mother and wife were fully supportive of my decision. Whatever little income then came from our sundry sources was enough for our sustenance,” says Bhatt, adding, “After that, my life no longer remained my own. I also needed to cut my umbilical cord with the past, so I put in my papers with GMOU and plunged headlong into what was to become my mission for the rest of my life.”

He adds: “I happened to meet leaders like Nabakrushna Choudhury, former Chief Minister of Odisha, and Manmohan Choudhury. They were leading the Sarvodaya Abhiyan in Odisha. Their sincerity touched me. I quit GMOU and joined Manmohan on his tour to our district as part of the Bhoodan Andolan in 1962. Manmohan was then chairman of Sarva Seva Sangha of India whereas I was a common man. I was highly inspired by his dedication and work for the upliftment of the downtrodden. We even spent nights in cowsheds in those days. This trip helped me develop a rapport with villagers.”

In April 1973, Bhatt brought about mass awareness in the Garhwal region against the indiscriminate felling of trees when he led a group of villagers in preventing the contractor of an Allahabad-based sports goods manufacturer from felling trees. The felling of the trees in large numbers was also part of the government’s policy of auctioning forests for commercial exploitation. Customarily, whole blocks of forests used to be auctioned to private contractors, euphemistically called forest lessees. This custom had begun towards the end of the 18th century when the British Indian government auctioned specified trees in a forest block to earn revenue and meet its growing requirement for sleepers for railways.

“The contractors cut down the banj (Himalayan Oak) tree and planted chir pine in its place. Chir Pine provided timber and resins for the industry, which was remunerative. Banj, on the other hand, was not lucrative. Thus, over the years, the complexion of the forest was being changed for commercial interests. Banj leaves fall on the ground year after year and create dark humus in which many bushes, plants and grass can grow. The thick humus soil soaks up the rain water and releases it slowly. It allows time for the rain water to percolate underground and down the slope slowly giving out clean water springs at a number of places. Another benefit is that the soil does not get eroded and is not washed away. Thus, the humus of banj leaves and undergrowth of banj trees serve useful ecological purposes, preventing flash floods and conserving top soil. In contrast, chir pine has fine needles which do not absorb rain water. Replacing banj with chir pine, results in drying up of water reserves, frequent floods and inferior soil. After women of the area came to realise how they would be affected by landslides and soil erosion caused by tree felling, they made it a point to ensure that the axe-men would not touch the trees.”

Recalling an interesting incident from the Chipko movement, Bhatt says, “By 1974, the Chipko movement had gained momentum in the Himalayan hills. At that time, the district administration decided to cut trees at Reni village located on the bank of river Rishiganga for commercial interests. While I had been creating awareness among the men about the impact of tree felling in the Himalayan hills, I did not realise that the women of Reni village had also been paying heed to my talks. When contractors arrived with their men to fell trees, no men were there to lead protests. However, as many as 27 women led by Gaura Devi protested and did not allow the contractors to cut trees shouting ‘Chipko Andolan Zindabad.’ Later, the district administration held a meeting with me in the presence of expert committees which also agreed with my concerns.”

Talking about Odisha, Bhatt says, “Planting trees alongside the riverbanks is the need of the hour to prevent floods in the state. The state government should think about how to increase the water level in major rivers like Brahmani and Baitaraini apart from Mahanadi and her tributaries so that they do not dry up. We must simultaneously ensure that these rivers are free from pollution caused by sewage, domestic waste and industrial effluents. Planting trees along the banks of rivers like Baitarini, Subarnarekha and Brahmani would help combat floods and cyclones and reduce the losses caused by natural calamities.”

Bhatt also talked about the role that governments and youth can play in conserving natural resources. “The youth should know how climate change will affect their future. We are exploiting nature for our well-being and other purposes. But, it is important for the youth to realise how important it is to save natural resources for our future generations as well. The government should include topics on local climate and environment in the college curriculum. They should be provided practical classes wherein they are taken to different riverbanks so that they get to know how planting trees alongside riverbanks helps to prevent flash floods. They should be encouraged to plant and grow trees. Besides, mangroves can play an important role in reducing the impact of cyclones. So, the government should plant more mangroves alongside beaches. Dense jungle not only helps reduce the impact of natural calamities but also prevents soil erosion.”

Bhatt adds: “There is a need to make the rural people understand the vision underlining the movement and its importance so that they relate to it and work for their own benefit in a localised manner. Rural women should be trained to deal with any sort of natural calamities.”

Bhatt then recounts some memorable incidents from his life. “Once I went to Kimana village, which was badly hit by flash floods in the river Alakananda in 1970. I was distributing relief materials among the needy after the village sarpanch gave me a list of names of beneficiaries. However, he excluded a woman who had delivered a boy just a fortnight before. I found her looking for rice under the debris of her house. I got to know from the villagers that her house had been completely damaged by the flood and she was deprived of relief due to past enmity with the sarpanch. I gave her three kilos of rice and a cow. Fifteen years later when I visited the village to attend a meeting, the woman came and met me. She was emotional and said, ‘Sir, do you remember me, I am Uma.’ Frankly speaking, I had completely forgotten about her. She recounted the whole incident and thanked me profusely for my gesture. She also introduced her 15-year-old son (who was then only 16 days old) and requested me to bless him.”

Recipient of the Ramon Magsaysay award, Padma Bhushan and Gandhi Peace Prize, Bhatt has a message for all: “We have to create a green environment for which eco development is the need of the hour. Every village should develop its own forest to prevent the occurrence of natural calamities.”

RASHMI REKHA DAS, OP