Washington: It may soon be possible to engineer plants that develop their own fertiliser by using atmospheric nitrogen to create chlorophyll for photosynthesis, according to Indian-origin researchers in the US.

The researchers from Washington University in the US engineered a bacteria that uses photosynthesis to create oxygen during the day and at night, uses nitrogen to create chlorophyll for photosynthesis.

The research, published in the journal mBio, could eliminate the use of some or possibly all manmade fertilisers, which have a high environmental cost.

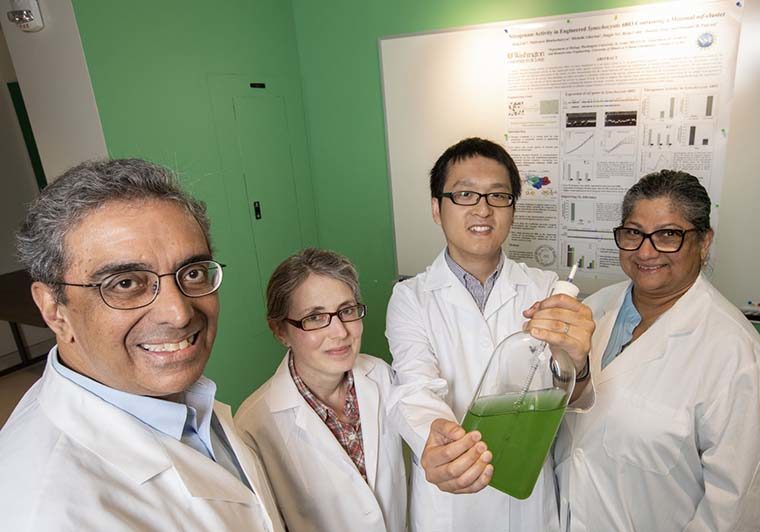

The discovery could have a revolutionary effect on agriculture and the health of the planet, according to Himadri Pakrasi and Maitrayee Bhattacharyya-Pakrasi from Washington University.

Creating fertiliser is energy intensive and the process produces greenhouse gases that are a major driver of climate change. Fertilising is a delivery system for nitrogen, which plants use to create chlorophyll for photosynthesis, but less than 40 per cent of the nitrogen in commercial fertiliser makes it to the plant.

After a plant has been fertilised, there is another problem: runoff. Fertiliser washed away by rain winds up in streams, rivers, bays and lakes, feeding algae that can grow out of control, blocking sunlight and killing plant and animal life below. However, there is another abundant source of nitrogen all around us, researchers said.

The Earth’s atmosphere is about 78 per cent nitrogen, and the Pakrasi lab engineered a bacterium that can make use of that atmospheric gas – a process known as ‘fixing’ nitrogen – in a significant step towards engineering plants that can do the same.

The research was rooted in the fact that, although there are no plants that can fix nitrogen from the air, there is a subset of cyanobacteria (bacteria that photosynthesise like plants) that is able to do so. Cyanobacteria can do this even though oxygen, a byproduct of photosynthesis, interferes with the process of nitrogen fixation.

The bacteria used in this research, Cyanothece, is able to fix nitrogen because of something it has in common with people.

Cyanothece photosynthesise during the day, converting sunlight to the chemical energy they use as fuel, and fix nitrogen at night, after removing most of the oxygen created during photosynthesis through respiration, researchers said.

The research team wanted to take the genes from Cyanothece, responsible for this day-night mechanism and put them into another type of cyanobacteria, Synechocystis, to coax this bug into fixing nitrogen from the air, too. To find the right sequence of genes, the team looked for the telltale circadian rhythm.

“We saw a contiguous set of 35 genes that were doing things only at night and they were basically silent during the day,” Pakrasi said.

The next steps for the team are to dig deeper into the details of the process, perhaps narrow down even further the subset of genes necessary for nitrogen fixation and collaborate with other plant scientists to apply the lessons learned from this study to the next level: nitrogen-fixing plants.

Plants may soon create own fertiliser from thin air