Santosh Kumar Mohapatra

Addressing students of the Ahmedabad University recently, Nobel laureate Abhijit Banerjee said, “People in India are in extreme pain and the economy is still below the 2019 levels, with small aspirations of people becoming even smaller now.” In July 2018, Nobel laureate Amartya Sen had said that India has taken a quantum jump in the wrong direction after 2014. He was critical of the Modi government because India was limping backward due to a decline in expenditure on health and education.

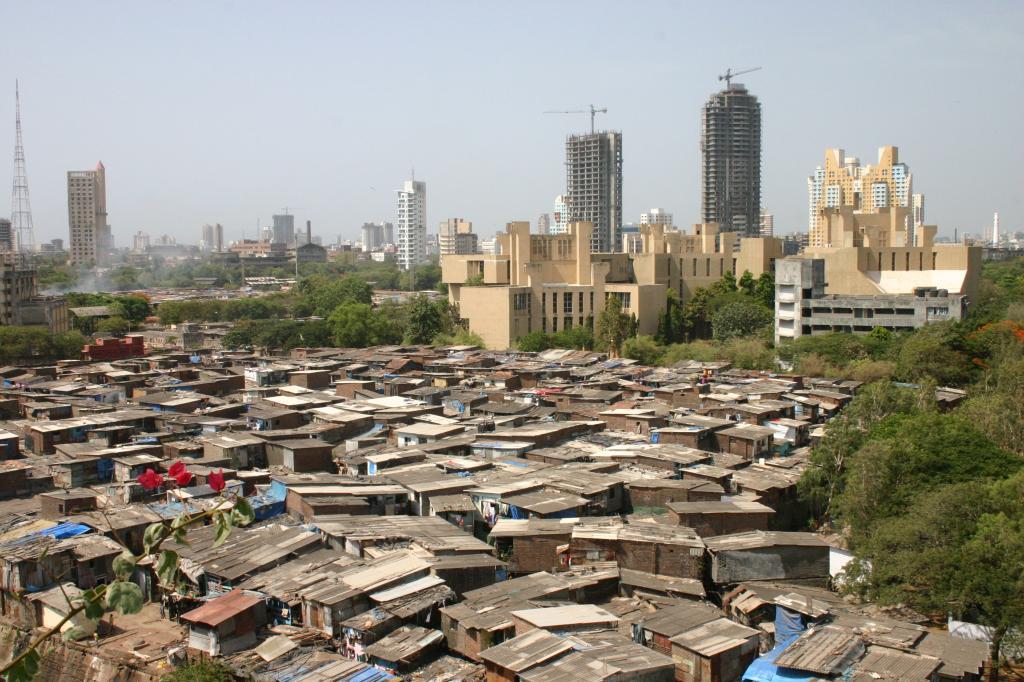

We know India has the ignominy of being a country of having the highest number of poor and hungry people in the world. In 2019, around 19.44 crore faced hunger in India. The Multi-dimensional Poverty Index (MPI) prepared by Niti Aayog revealed that one in every four people in India was multi-dimensionally poor in 2016-17. As of 2018, more than 16.3 crore Indians did not have access to safe drinking water. An estimated 3 million Indians are homeless. Women, in particular, are vulnerable to appalling violence and sexual exploitation.

According to the World Inequality Report 2022 released by the World Inequality Lab December 7, “India stands out as a poor and very unequal country, with an affluent elite, in the world.” The bottom half of the Indian population owns ‘almost nothing’ of the national wealth, whereas the top one per cent earned more than one-fifth of the total national income.

Measured in terms of purchasing power parity, the average national income of the Indian adult population is Rs 204,200, while the average household wealth in India is equal to Rs 983,010. The income inequality can be understood from the fact that, in 2021, while the top 10 per cent and top 1 per cent of the population held 57.1 per cent and 21.7 per cent of total national income, respectively, the bottom half held just 13.1 per cent. While the bottom 50 per cent earns Rs 53,610, the top 10 per cent earns Rs 1,166,520. The middleclass that constitutes 40 per cent earns 29.7 per cent of income. In 2021, the bottom 50 per cent of the nation held an average wealth of Rs 66,280 or 5.9 per cent of the total pie. The middleclass had an average wealth of Rs 7,23,930 or 29.5 per cent of the total. The top 10 per cent owned 64.6 per cent of the total wealth, averaging Rs 63,54,070 and the top 1 per cent owned 33 per cent, averaging Rs 3,24,49, 360.

The report has also flagged a drop in global income during 2020, with about half of the dip in rich countries and the rest in low-income and emerging economies. But what is disconcerting is that when India is removed from the analysis, it appears that the global bottom 50 per cent income share actually slightly increased in 2020.

Most of time, those who opposed the so-called economic liberalisation and advocated higher progressive taxes on the rich and corporates were dubbed as leftists and condemned. But now the World Inequality Report defies the very logic of economic liberalisation and justifies leftist views on economic liberalisation. Evidence from across the world has shown, fast GDP growth alone doesn’t help, especially when it comes to tackling inequalities in accessing education and health.

According to the report, the deregulation and liberalisation policies implemented for India’s economy since the mid-1980s have led to one of the most extreme increases in income and wealth inequality. While the top 1 percent has largely benefited from economic reforms, growth among low-and middle-income groups has been relatively slow and poverty persists.

Going back in time, the report shows that income inequality in India under colonial rule (1858-1947) was very high, with a top 10 per cent income share around 50 percent. After Independence, due to socialist-inspired Five-Year Plans, this share was reduced to 35-40 per cent. Owing to poor post-Independence economic conditions, India embarked upon deregulation and loosening controls in the form of liberalisation policies. Now, a few persons have amassed wealth leading to the impoverishment of many.

The wealth of the richest individuals in the world has grown at 6 to 9 per cent per annum since 1995, whereas average wealth has grown at 3.2 per cent per year. Since 1995, the share of global wealth possessed by billionaires has risen from 1 per cent to over 3 per cent. This increase was exacerbated during the pandemic. In fact, 2020 marked the steepest increase in global billionaires’ share of wealth on record.

What is reprehensible is that the share of public wealth across countries has been on a decline for decades now. This trend has been magnified by the COVID crisis, during which governments borrowed the equivalent of 10-20 per cent of GDP, essentially from the private sector.

Currently, governments have more debts than assets as rich, wealthy and corporates are not paying their fair share and the government is taking recourse to debt-induced growth where the burden of debt falls on the masses through the decline in welfare expenditure while benefits of growth are garnered by the rich.

The ultra-low interest regime is also helping the rich to amass wealth at the cost of savers. Similarly, another reason for rich and corporates accumulating wealth at a faster rate is not due to hard work but bubbles and crashes of the stock market. The reduction of corporate taxes from 30 per cent to 22 per cent introduced in 2019 in India has not translated into any boom in private investment. There is an accretion to profits of corporates.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi has never discussed the issue of income and wealth inequality. In his Independence Day speech in 2019, Modi said, “Let us never see wealth creators with suspicion. Only when wealth is created, wealth will be distributed.” But the World Inequality Report reveals that national wealth has not been evenly distributed. Hence, the solution lies in the imposition of wealth and inheritance tax, keeping real interest rate positive, and taxing the windfall gains in share markets.

The writer is an Odisha-based economist and columnist. Views are personal