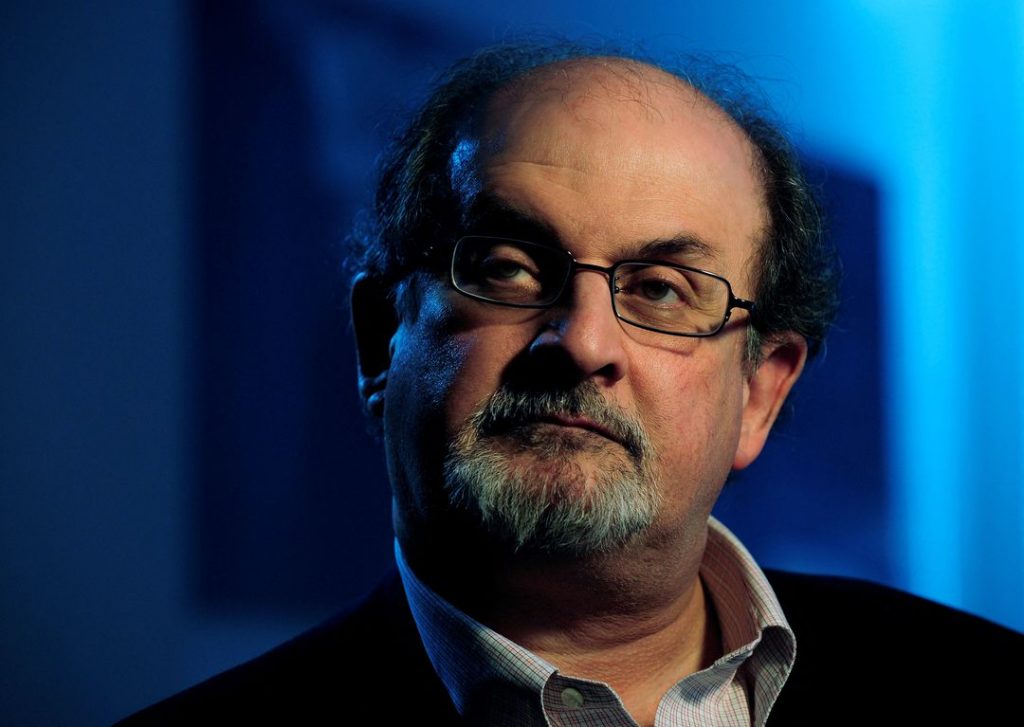

Hadi Matar, the 24-year-old Lebanese-American charged with attempting to murder the British author Salman Rushdie, appears to have been acting on his own. Matar claims to be an admirer of the late Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the Iranian supreme leader who issued the murderous fatwa against Rushdie in 1989 following the publication of the author’s novel The Satanic Verses. But there is no evidence that the attacker is linked in any way to the Iranian government. Nonetheless, at least one commentator has called the assassination attempt an “act of state-promoted terrorism.”

That description sounds about right. State-promoted is not the same as state-sponsored, much less state-directed. Even though the Iranian government has not in fact tried to kill Rushdie, Khomeini’s fatwa still stands, and the state must bear some responsibility for inspiring murderous fanatics like Matar.

Killers or would-be killers have been fired up by violent language before, of course. Anders Breivik, the Norwegian who murdered 69 young people at a social-democratic summer camp in 2011, was an avid reader of writers who warned that Muslims, coddled by European liberals, posed a dire threat to Western civilization. Does this mean that individual writers and bloggers whose output convinced Breivik that he should kill to save the West were partly responsible for his horrific deeds?

Much has been said, and rightly so, about Rushdie’s defence of free speech, and the price he has paid for his fortitude. In the United States, the Constitution protects Right-wing activists who claim to be “at war” with Muslims or Leftists, whom they see as an existential menace to America and the Christian way of life, so long as the culture warriors do not create “a clear and present danger.” They may not threaten violence against any individual, because that would pose “a real, imminent threat,” but they can freely spout their hatred of any creed they want.

European laws on free speech are tighter. In France, and many other European countries, it is prohibited to “defame or insult” a person or group on the grounds of ethnicity, nationality, race, religion, sex, sexual orientation, or disability. You may say that Islam, Christianity, or any other religion is abominable, but you may not insult an individual for his or her belief.

There is a difference between insulting someone and offending them. Whereas an insult is a deliberate attempt to wound, to offend is to hold an opinion that someone might find offensive, even though no offense is intended. A writer can be held responsible for an insult, but not for an offense. There is no evidence that Rushdie intended to insult anyone in The Satanic Verses, but he offended many people, whether they read the book or (usually) not.

But, for many people, religion is much more than a set of rules or beliefs to which they adhere. Like nationality, it can constitute the core of a person’s identity. When someone’s sense of self is challenged, they quickly take it as an insult, even if none is intended.

Neither Rushdie nor any other writer or thinker should be constrained by this. People must be protected from imminent danger, and perhaps, as is the case in Europe, also from personal defamation or insult, but there is no reason why particular ideas and beliefs should be protected from criticism or even ridicule.

There is, however, another distinction to be considered. The impact of speech depends on who says what to whom.

Even though Breivik may have been inspired by extreme anti-Islamic or anti-liberal views promoted by certain individuals, those writers and bloggers are not responsible for the murders he committed. One might criticize them for not considering the possible consequences of spreading fear and loathing. They could be morally culpable. But their views carry no authority.

The danger is far greater when a politician or a religious leader stokes hatred. The consequences of Khomeini’s fatwa are patently clear. The Japanese translator of The Satanic Verses was murdered in 1991, the book’s Italian and Norwegian translators barely survived violent assaults, and Rushdie’s would-be killer nearly succeeded.

But Iranian clerics are not the only culprits. US politics is now being inflamed by verbal violence that is just as lethal.

Open and democratic societies depend on a consensus that conflicting interests and competition for power can be resolved peacefully. Changes of government, after lawful and fair elections, must be accepted. Those who hold opposing political views should not be treated as existential enemies.

But that is not a view widely shared within the US Republican Party, much of which remains in thrall to former President Donald Trump. Extremist GOP members of Congress routinely describe Democrats – and even Republicans who defy Trump – as “traitors.” During his 2016 election campaign, Trump himself called for his opponent to be “locked up.” Various Republican politicians have talked about a “civil war” having begun, and emphasise citizens’ duty to take up arms. The consequences of using this kind of language became evident on January 6, 2021, when a violent mob took Trump and his political boosters at their word and stormed the US Capitol.

There is a difference between cynics or deluded fanatics expressing extreme opinions and people in positions of authority doing so. Individuals who spread lies and invective on the internet or television are repellent and sometimes dangerous, but political and religious leaders who stir hatred authorise people to kill.

The writer is an editor and author. ©Project Syndicate.