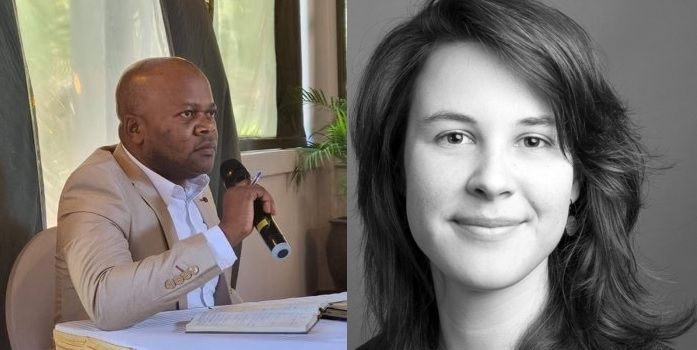

By Johanna Sydow & Nsama Chikwanka

The environmental and human toll of mineral extraction is becoming clearer – and more alarming – by the day. Roughly 60% of Ghana’s waterways are now heavily polluted due to gold mining along riverbanks. In Peru, many communities have lost access to safe drinking water after environmental protections were weakened and regulatory controls were suspended to facilitate new mining projects, contaminating even the Rímac River, which supplies water to the capital, Lima. These environmental crises are exacerbated by deepening inequality and social divides in many mining-dependent countries. The Global Atlas of Environmental Justice has documented more than 900 mining-related conflicts around the world, about 85% of which involve the use or pollution of rivers, lakes, and groundwater. Against this backdrop, major economies are rapidly reshaping resource geopolitics.

The US, while attempting to stabilise the fossil-fuel-based global economy, is also scrambling to secure the minerals it needs for electric vehicles, renewable energy, weapons systems, digital infrastructure, and construction, often through coercion and aggressive negotiating tactics. In its quest to reduce dependence on China, which dominates the processing of rare-earth elements, environmental and humanitarian considerations are increasingly brushed aside. Saudi Arabia is likewise positioning itself as a rising power in the minerals sector as part of its efforts to diversify away from oil, forging new partnerships – including with the US – and hosting a high-profile mining conference.

At the same time, the Kingdom is actively undermining progress in other multilateral fora, including this year’s COP30 and the pre-negotiations of the UN Environment Assembly (UNEA7). In Europe, industry groups are lobbying for further deregulation, with fossil-fuel companies like Exx onMobil, TotalEnergies, and Siemens using misleading tactics to undermine newly established mechanisms designed to protect the rights of communities in resource-producing regions. We should be worried that the companies and countries which helped drive global warming, environmental degradation, and human-rights abuses now seek to dominate the mineral sector. Allowing them to do so will put all of humanity, not just vulnerable populations, at risk. Governments must not remain passive. They must reclaim responsibility for steering the primary driver of mining expansion: demand. Reducing material consumption, especially in developed countries, remains the most effective way to protect vital ecosystems and prevent the long-term harms that extraction inevitably causes. Yet despite overwhelming evidence that ramping up resource extraction threatens water supplies and public safety, governments around the world are weakening environmental protections in a bid to lure foreign investment, thereby endangering the very ecosystems that sustain all life on Earth. When people cannot trust political leaders to protect their rights, they are highly likely to resist, with the resulting social conflict causing investment to falter. The backlash against Rio Tinto’s Jadar lithium-mining project in Serbia is a prime example.

Many Serbians believed their government was putting corporate interests first by pushing ahead with the project despite its failure to meet even basic sustainability standards. The public outcry halted development and left the company facing steep losses. Only robust legal frameworks, backed by effective enforcement, can create the conditions for stable and rights-respecting development. That means safeguarding Indigenous rights; ensuring the free, prior, and informed consent of all affected communities; protecting water resources; undertaking spatial planning, establishing no-go zones; and conducting independent, participatory, and transparent social and environmental impact assessments. All countries, especially mineral producers that have historically been excluded from the negotiating table, should seize this moment. UNEA7 provides a window for achieving resource justice.

Johanna Sydow is from the Heinrich Böll Founda tion. Nsama Chikwanka is from Publish What You Pay Zambia.