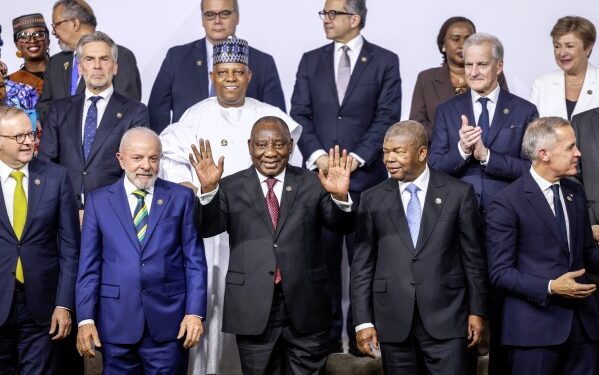

This month’s G20 Summit in Johannesburg marked several his toric firsts. For starters, it was the group’s first-ever summit in Africa, and the first to include the African Union as a full-fledged member. It also set less encouraging precedents: it was the first meeting boycotted by a key founding member of the United States –on spurious grounds, and the first in which that same country tried to prevent the host from issuing a final declaration. Equally unprecedented was South Africa’s decision to ignore the American threat and issue one anyway. As G20 president, South Af rica invited delegations from Africa and other parts of the world to participate as guests, underscoring the continued importance of multilateral dialogue and cooperation.

South Africa’s inclusive approach paved the way for another landmark moment: for the first time, G20 leaders formally addressed the issue of global inequality. The impetus was the recent report by the Extraordinary Committee of Independent Experts on Global Inequality. Chaired by Nobel laureate economist Joseph Stiglitz, the committee (of which I was a member) synthesised a large body of research and drew on consultations with 80 prominent scholars to present a comprehensive picture of economic disparities worldwide.

The conclusions are hardly reassuring: although global inequality has declined since the early 2000s, this is largely due to rising incomes in China. While inequality between countries has fallen, the gulf between the richest and poorest countries remains unacceptably wide. Nine out of ten people now live in countries with high inequality – even by the World Bank’s relatively conservative standards.

The distribution of income within countries is equally distorted. Wage shares of national income have declined in most economies over the past few decades, while capital income has become increasingly concentrated. Large firms now account for the bulk of corporate profits, with multinational corporations taking the lion’s share.

These developments reflect a broader trend: the concentration of income and wealth at the very top. Of the two, wealth is far more unequally distributed, as its explosive growth in recent decades has been overwhelmingly skewed toward those who were already rich. More than 40% of the wealth generated since the start of the century has gone to the wealthiest 1%, while the bottom half of the world’s population received just 1%.

Even within the top 1%, the gains have been largely captured by the ultra-wealthy – arguably the most extreme concentration of wealth in human history. The result is a class of global plutocrats whose unprecedented resources enable them to shape laws, institutions, and policies; influence public opinion through their control of media; and tilt judicial systems in their favour. Contrary to neoliberal economists’ claims, high inequality does not spur economic growth; it suppresses it. When inherited wealth is privileged over earned income, incentives to innovate shrink. And since the consumption and investment patterns of the ultra-wealthy are vastly more carbon-intensive and resource-depleting, extreme inequality also undermines environmental sus tainability and climate action.

As we argue in our report, inequality has become an emergency that must be treated with the same urgency as climate change. Like the climate crisis, the inequality crisis can be partly attributed to the legacy of colonialism, as well as long-standing socio-cultural structures. But above all, it reflects the legal, institutional, regulatory, and policy choices that have allowed a few to enrich themselves at the expense of everyone else.

There is no shortage of examples. Financial liberalisation and repeated government bailouts have protected wealth at the top. Stringent intellectual-property regimes have created monopolies over knowledge. The privatisation of essential public goods and services has further entrenched disparities. Outdated tax systems have enabled large multinational firms and wealthy individuals to avoid paying their fair share.

Taken together, these policies have dramatically shifted the balance between public and private wealth. As governments privatised assets and accumulated debt – often to subsidise or guarantee private capital – public balance sheets deteriorated while private fortunes soared.

The good news is that since these trends are the product of political choices, they can be reversed. But doing so requires a clearer understanding of the problem. Despite the explosion of research and the emergence of promising analytical methods, major blind spots remain, making it harder to design effective policies that curb inequality. That is the central message of our report. While it includes many policy recommendations, its most urgent and practical proposal is the creation of an international panel of experts on inequality.

Loosely modelled on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the proposed panel would rely on voluntary contributions from researchers around the world and serve as an authoritative, accessible source of information for governments and the public. Such knowledge would support policymakers genuinely seeking to reduce inequality. Perhaps more importantly, it would empower citizens to demand the policy changes and reforms needed to build just and equitable societies.

The writer, Professor of Economics at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, is Co-Chair of the Indepen dent Commission for the Reform of International Corporate Taxation.