These are critical times. As societies, we are no longer able to band ourselves together. We feel uninspired to live responsibly as a collective. The crisis is more acute in Odisha. Middle-class Odisha, at least in the past three to four decades, has been deeply invested in the idea of individualised success. It harbours a stereotypical view that political activism is essentially a distraction for the youth. Politics is viewed as something that only people of privilege practice irresponsibly. As a result, the level of political and social awareness among the youth is low.

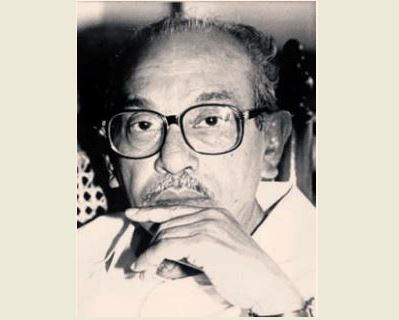

The criticality of the times has been worsened by the limited exposure people have to the lives and works of strong leaders. Luminaries from the past who made significant differences to the state — and to the closer communities in which they worked — are less discussed. One such figure is Harish Chandra Baxipatra, who, besides contributing significantly to the development of Odisha, was a major source of inspiration for activism.

Baxipatra took upon himself the task of educating people about their political rights and responsibilities. He understood that it is important first to let people recognise their own identities as members of various collectives so that they can protect and preserve them. Decades after national independence, the Adivasis of Koraput, for example, had little knowledge that they were part of a democracy in which they had equal rights with other citizens of the country. Baxipatra sensitised them about their roles, mobilising them to join the mainstream of political democracy with the fiery slogan “Chinhaa Pada, Chimraa Pada Nahin” (“Get identified, don’t fall silent”).

He had a knack for identifying young people who wanted to work for society. In many small and big towns of Odisha, enthusiastic youth flocked to him, and he “trained” them extensively in identifying social issues, articulating those issues to the public and to the powers-that-be, organising politically, and getting issues resolved. It is widely known that a whole generation of political leaders emerged from Baxipatra’s mentorship.

An ideal leader is one who does not ask to be followed; the leader’s actions and speech automatically attract people. That holds true for Baxipatra as well. From touring the remote villages of the 1970s and 1980s on kutcha roads to spending protracted periods in the corridors of power, he could navigate both worlds untrammelled only because his sole goal was a developed Odisha. Such principles motivated the youth. Many of them, in successive years, went on to mobilise more people in social and political activities. Not all of them grabbed media headlines, but they have been doing sincere work on the ground even now.

In addition to working at grassroots level, scholarship shaped Baxipatra’s commitment to activism. As someone who wrote regularly and read avidly, his knowledge base gave younger people another reason to believe in the gravity of his actions and to embrace them.

It is time that we assured the current generation of the sanctity of political activism. Political activism is a good thing, and it is our job to identify principled and passionate leaders and emulate them.

Mahasweta Baxipatra